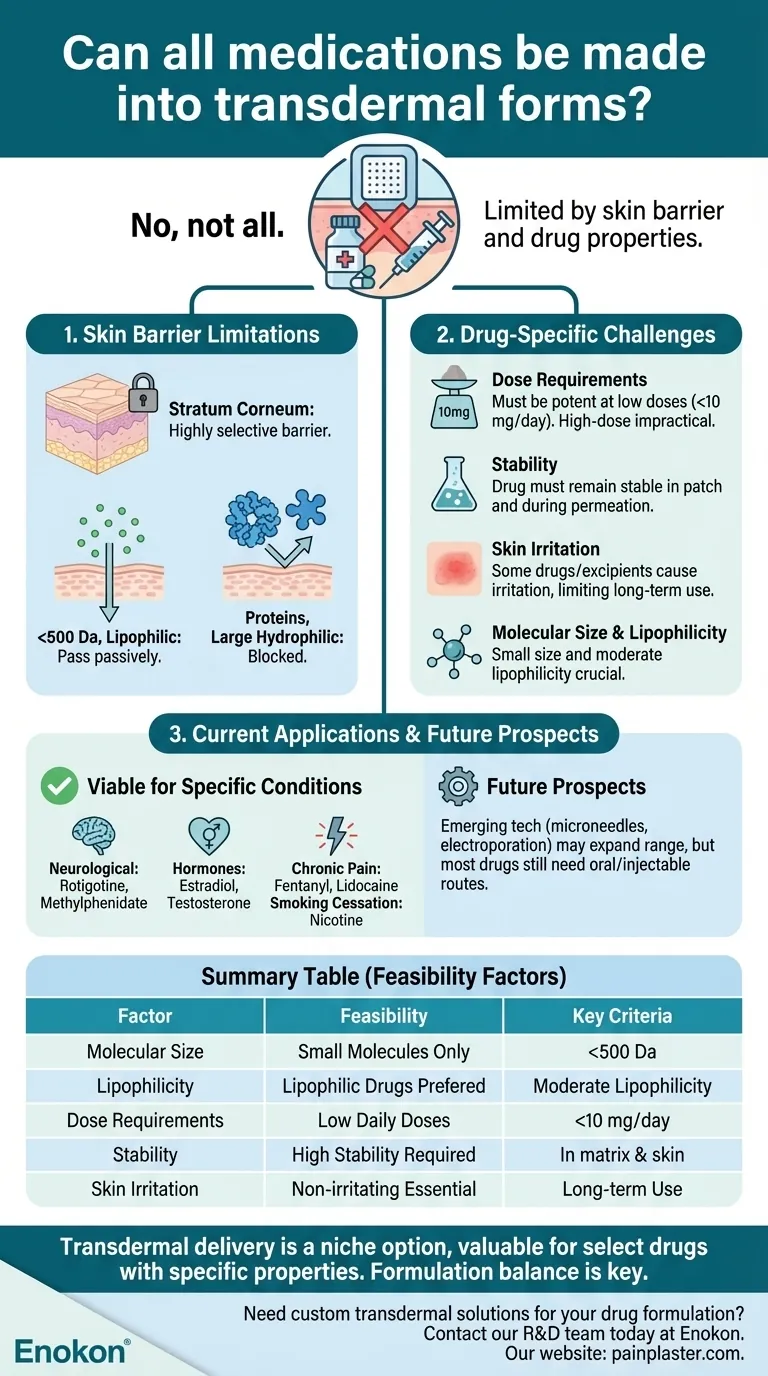

Not all medications can be effectively formulated into transdermal forms due to the skin's natural barrier properties and the complex physicochemical requirements drugs must meet for successful absorption. While transdermal delivery offers advantages like sustained release and avoidance of first-pass metabolism, it is limited to specific drug classes that can penetrate the skin efficiently and maintain therapeutic efficacy. Current transdermal medications primarily target conditions such as chronic pain, hormonal therapy, and neurological disorders, but many drugs remain unsuitable due to molecular size, solubility, or skin irritation risks.

Key Points Explained:

-

Skin Barrier Limitations

- The stratum corneum, the outermost skin layer, acts as a highly selective barrier that restricts the passage of most molecules.

- Only small (typically <500 Da), lipophilic drugs with adequate solubility can diffuse passively through this layer.

- Proteins, peptides, and large hydrophilic molecules (e.g., insulin) generally cannot be delivered transdermally without advanced technologies like microneedles or chemical enhancers.

-

Drug-Specific Challenges

- Dose Requirements: Transdermal drugs must be potent enough to achieve therapeutic effects at low doses (often <10 mg/day). High-dose medications (e.g., antibiotics) are impractical.

- Stability: The drug must remain stable in the patch matrix and during skin permeation.

- Skin Irritation: Some drugs or excipients cause irritation or sensitization, limiting long-term use (e.g., NSAIDs).

-

Current Applications

Transdermal systems are clinically viable for:- Chronic conditions: Nicotine (smoking cessation), fentanyl (pain), scopolamine (motion sickness).

- Hormones: Estradiol (menopause), testosterone (hypogonadism).

- Neurological disorders: Rotigotine (Parkinson’s), methylphenidate (ADHD).

- These drugs meet the criteria of small size, moderate lipophilicity, and low daily dose requirements.

-

Species-Specific Variability

- Animal transdermal delivery is further complicated by fur thickness, skin pH differences, and grooming behaviors.

- Veterinary patches (e.g., fentanyl for cats) require species-specific formulations.

-

Future Prospects

Emerging technologies like electroporation, sonophoresis, and nanoparticle carriers may expand the range of transdermal drugs, but most medications will still require oral or injectable routes due to inherent limitations.

For now, transdermal delivery remains a niche option—valuable for select drugs but impractical for many others. Have you considered how formulation scientists balance these constraints when designing new patches? It’s a fascinating interplay of pharmacology, chemistry, and biomechanics that quietly shapes modern medicine.

Summary Table:

| Factor | Transdermal Feasibility |

|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Only small molecules (<500 Da) can passively penetrate the skin. |

| Lipophilicity | Lipophilic drugs diffuse more easily through the stratum corneum. |

| Dose Requirements | Low daily doses (<10 mg/day) are practical; high-dose drugs (e.g., antibiotics) are not. |

| Stability | Drug must remain stable in patch matrix and during skin permeation. |

| Skin Irritation | Drugs causing irritation (e.g., NSAIDs) are unsuitable for long-term use. |

| Current Applications | Pain (fentanyl), hormones (estradiol), neurology (rotigotine), smoking cessation (nicotine). |

Need custom transdermal solutions for your drug formulation?

At Enokon, we specialize in bulk manufacturing of reliable transdermal patches and pain plasters tailored for healthcare brands and pharmaceutical distributors. Our technical expertise ensures optimized drug delivery, whether you're developing a new product or refining an existing formulation.

Contact our R&D team today to discuss how we can support your project with scalable, high-performance transdermal systems.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Far Infrared Heat Pain Relief Patches Transdermal Patches

- Heating Pain Relief Patches for Menstrual Cramps

- Herbal Eye Protection Patch Eye Patch

- Menthol Gel Pain Relief Patch

- Icy Hot Menthol Medicine Pain Relief Patch

People Also Ask

- What types of pain can the Deep Heat Pain Relief Back Patch be used for? Targeted Relief for Muscles & Joints

- How do Deep Heat Pain Relief Patches provide pain relief? Discover the Drug-Free Mechanism

- How quickly does the Deep Heat Pain Relief Back Patch activate and how long does it provide warmth? Get 16-Hour Relief

- How does capsaicin work in the medicated heat patch? The Science Behind Pain Relief

- How does the Deep Heat Back Patch work? A Drug-Free Solution for Targeted Pain Relief